Updated: October 1, 2018

You may have heard about this. Google is considering an idea of changing how people interact with websites. More specifically, how people interact with URLs, the human-readable Web addresses by which we largely identify and remember websites we go to. The ripple effect around this proposal has been quite interesting, to say the least. And it got me thinking.

One, the actual backlash against the change is more revealing than the change itself. Two, is there really any real merit in trying to make URLs somehow more meaningful and/or useful than their current form? To that end, you are reading this article.

URL at a glance

Humans associate memories with words rather than numbers. It is much easier for us to remember entire sentences or paragraphs than a string of numbers. This is because our language is constructed mostly of words. We struggle with any sequence of numbers that is longer than eight or nine digits. The simple reason is, with letters, the uniqueness of information is relatively small - 1001 and 1002 are only one letter apart, so to speak, but it is only the last piece that gives meaning to the difference. With words, there are relatively few combinations that will be ambiguous beyond a short sequence of characters and/or sounds.

Therefore, as the Web came about, it became more logical to use words - strings - to identify Websites rather than the machine interpretation. It's a funny cycle. We transform words (code) into machine language, and then we do the reverse so that people can interact with computers in a meaningful way. Going about the Web using numbers is the machine way. Strings are the human way.The problem is - URLs are a hybrid form between human and machine language. On one hand, you have the human element, the address itself (like dedoimedo.com), but all the rest is pretty much instructions for the remote server to find, search and present information back to the user. This does present a problem in that people interact with websites in a way that does not always make sense to the ordinary human brain.

Another problem is - URLs do not have any embedded information fidelity. Much like physical addresses in the real world. If you go to 17 Orchard Drive, it does not tell you WHAT that address is. It could be an office, it could be a private residence, it could be a dance hall. There's no information about the CONTENT either, as in what you will find there - people, rubble, a sacrificial altar, etc.

In the same way, URLs do not reflect the destination (the site you're connecting to) in any way. Sometimes, there might be some correlation, but overall, it's not meaningful unless you know what the site is all about, and what it's meant to do. This is true for small sites as well as giant companies.

For instance, Google does not really tell you it's a search engine. Yahoo does not tell you it's a search engine. What does Bing mean? Is Amazon a river, a forest or a huge online market place? You have come to trust these sites through usage and general reputation, not because there's any proto-value in the URL information. But it gets better, or rather, worse:

- No correlation between the site string and the site purpose.

- No correlation between the site string and the site name (or business behind it).

- No correlation between the website page title and the site name.

- No information about the purpose of the site.

Furthermore, when you land on a specific page, there might be no correlation between the page title, URL and the content. You could go to some site, to a page called kittens.html, but it might be about cat-shaped decals for cars, or indeed about small furry things. Or something else entirely. And the site might actually be called Dany's shop, and the URL could be something like mysitenstuff.org.

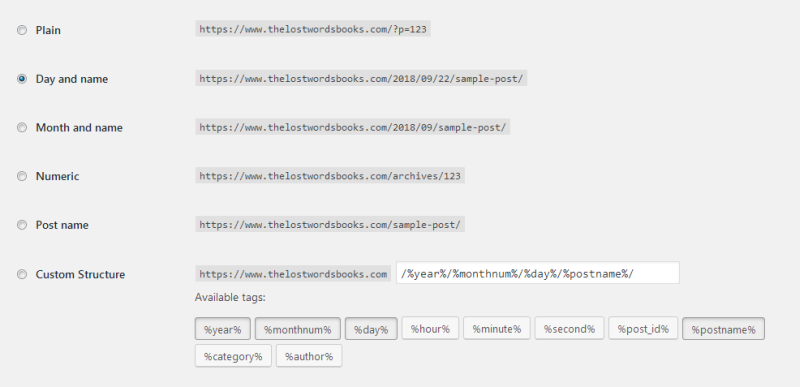

And it gets worse still. For now, we've only discussed the human element of the equation. Then, there's the machine part. Subdomains. Stuff like m, www, www3. Protocols like http, https, ftp. Delimiters, sub-directories. Non-uniform way by which sites present their pages - dates, random numbers, strings, etc. Then, you also have instructions. A page may have something like &uid=1234567&ref=true appended to the end of the URL string, which means nothing to you as the user, but it tells certain things to the Web servers and/or the application that is serving or parsing the content.

All of these URL options would resolve to the same content, but they all look and render differently.

Finally, there is no measure of trust. Websites are equal in their worth until they have been validated in some way. Early on, as online shopping became more popular, the concept of digital certificates came about, with trusted authorities vouching both trustworthiness and security behind encrypted and tamper-proof badges. Community efforts and page ranking (sometimes proprietary) became secondary measures of worth associated with domains (sites) and their content, but essentially, this is in no way reflected in the URL itself.

So the question is, do we need a change? Maybe. Maybe not. The Internet works and scales fine.

The answer lies in the solution. But first, a bit more philosophy.How did you react when you heard about the proposal?

From what I've seen, there are two major camps here. Those who welcome the change, feeling this will make the Web better (the quantity of better needs to be defined, otherwise it's just empty talk). And those who oppose the change. The second groups can be split into three: people resistant to change for the sake of, those who oppose the technical merit and the supposed benefits, and the third group that do not trust a for-profit company proposing or leading this change.

Indeed, this poses a much bigger philosophical question. Should Google be allowed to lead this?

After all, over the years, numerous for-profit companies have created nice products that we use today without even thinking about it. The early furor and debate are long forgotten. But there was money involved, it was a strong motivating factor, and things were done to strengthen the company's bottom line. The same will inevitably happen with any which company that has a responsibility to its shareholders, whatever its name is. Google has the leadership position because of its massive influence in the mobile world and the search arena. But this could be any which company, and ultimately, the underlying factors are the same. To some people, this is all that matters. If it's for-profit, it cannot be an impartial solution that benefits humanity. Maybe, as a side effect, but not as a primary goal.

And this is the really intriguing one. The resistance is more a reflection of Google over the years rather than anything to do with technology itself. Seemingly, from do-no-evil (gone from the company's manifest) to just another run-of-the-mill big-boy-suit company.

Another example that strengthens the case is Google's insistence on AMP, its own mobile-optimized project that wraps ordinary HTML in special AMP directives. While it has some merit when it comes to page loading and such, overall, this is really bad. It's the repetition of the problem we saw with Internet Explorer 6, where Microsoft came up with a whole range of new directives that did not comply to Web standards, creating a browser-specific HTML/CSS chaos that has only recently been unraveled - partially.

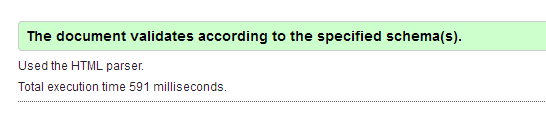

When I started Dedoimedo back in 2006, this was a big issue. Almost every site back then had IE6/7/8 overrides in their HTML. I decided not to implement those and stick to the W3C specifications, regardless of the possible penalty in visitors or whatnot, because the only way to do design in a common and standardized fashion is how the legendary Tim Berners-Lee envisioned it. The history proved me right. Even today, I make sure all my pages have valid HTML and CSS, which is something that you rarely see on the market nowadays. And if you use special overrides for this or that browser, then you are helping make the Internet less good.

Valid HTML, an endangered species.

Now, Google is recreating the HTML/CSS compliance divergence issue with AMP. The Web must be neutral and compliant to impartial, international standards. It should never be shaped according to whatever whichever company wants.

Therefore, the URL is merely a catalyst to rising mistrust against big corporations, especially those in the business of private data. That is the problem that needs to be addressed first so that we can separate emotion from technology. Otherwise, all future proposals will be flawed, as they will seek to address emotional needs rather than technical needs.

I don't have a solution for this - only Google can change Google. If they want to, of course.

Things change

We must not forget this. Benevolent ideas get swept in the momentum of life, becoming perverted versions of their early concepts. This sometimes happens through deliberate design, and sometimes by accident, through a million little decisions and constrains that could not have been seen or planned in advance. Think about pretty much any product you're using. Look at what it was five or ten years ago, if it existed that far back. Do you see a change? Do you like it? And then remember that you have also changed as a person, and how you perceive the world today is not quite like how you felt a few years earlier.

Google's solution - or anyone's for that matter - may be the best thing in the world. Seventeen or twenty years from now, it might change in a way that is impossible to predict, despite best intentions and all the deep learning in the world. There needs not be any malice in it. Just the slow creep of how things are done, people getting used to and accepting the new norms as old traditions, and moving on, until the original thing has long been forgotten.

Therein lies the big problem. Whatever the agreed proposal is today, even if Google's solution is PERFECT, there's nothing to stop any company from making a private, proprietary implementation, including Google itself for that matter. Or any competitor.

The privatization of the Internet is actually already happening. The Internet is getting smaller. First, you're consuming most of your information through brokers - search engines, news portals. You will rarely find new content unless it's listed on popular search sites, and even then, high up on the list. On the mobile, it's even worse. People hardly browse any more. They use apps, served by a single, centralized store.

Just look at what a typical smartphone or a smart TV is - a tightly controlled platform with curated and filtered content. When you launch a phone app, you have no idea what it's doing in the background or what URLs it's connecting to. Either you trust the platform to do what it says it will do, or you do not use it, which is becoming harder given how intrusive and necessary technology has become in everyday life. And this happened in, what, only ten or fifteen years since the Internet really boomed? Imagine what will happen in twenty or fifty years.

Internet as a human right

The Internet, so to speak, has already been added to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But that's nowhere near enough.

We already have the Internet task force. We have standards. We also have privacy laws, mostly national. But there is no supra-governmental body that guarantees digital freedom and non-interference by private parties into the neutrality of the Web down to the individual level. It is quite possible that this might never happen, as the pie is just too big and succulent to let go.

Well if you ask me, the only way to really make sure certain parts of the Web are truly untouchable is to enshrine them in a digital Geneva-like convention. This sounds naive and idealistic, but then, today, you are the mercy of whoever controls your Internet and how they decide to give it to you.

My proposal

All right, finally, the technical bits.

Anyway, the URL structure is largely: machine | human | machine.

The driving factors are: neutrality, security, integrity, ease of use. Security and integrity are already solved relatively well by digital certificates - but they can be improved. Neutrality is embedded in the human part of the URL string, and the ease of use rests in the first and the last part.

Machine part 1

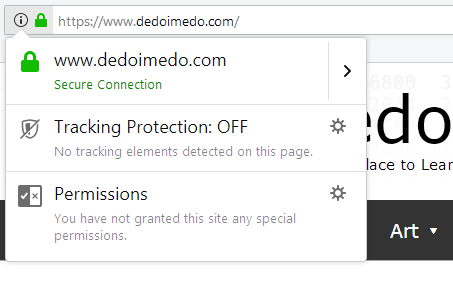

As you know, modern browsers are already trying to separate the machine part from the human part of the Web address string by not showing the https:// and/or www parts of the address, as these browsers rarely if ever serve protocols other than http or https. This isn't too bad. However, the Secure-Not Secure concept is not clear enough. It's alarming and comforting but not for the right reasons - we will talk about this in the human part section.

HTTP:// or HTTPS:// mean nothing to 99% of people. They are useful if you hand the URL string over to other applications, so they can use the right protocol to connect. Moreover, we actually have a redundancy here. Certificates are already doing the job of ascertaining connection security.

The answer is is to either remove the prefix (machine part 1) completely and just use certificates, or for symbolic reasons, replace the prefix with something like web - the actual delimiter and whatnot bear separate scrutiny. This could potentially open a venue to future implementations of other non-web protocols, like virtual reality, pure-media streaming, chat, and so forth. And also keep in line with browser-specific internal pages like config, chrome, etc.

Human part

The human part must be inviolate - whatever the site page address is, it must remain and it must always be shown to the user without any obfuscation. There should be guidelines for good URL practices that applications could obey, including matching domain name, purpose, logic, date and title, which some servers do. But this is just like physical addresses. We don't get to choose how streets are named, or how the home address is formed, and there are so many options worldwide. Same here.

This is part of what we are - and changing this language also breaks communication. There is no universal piece of objective information in a domain name, page title or similar. It's all down to what we want to write, and so, trying to tame this into submission is the wrong way forward.

But what about trust, integrity, spoofing?

If you mistype a site name, you could land on a wrong page. Or people ignore security warnings and give their credentials out on fake domains. Are there ways to work around these without breaking the human communication?

Well, certificates help - but they won't stop you going to a digitally signed site that is serving bogus content. Nor can they stop you from giving out your personal data. But on its own, technology CANNOT stop human stupidity or ignorance. It can be mitigated, but the unholy obsession with security degrades the user experience and breaks the Internet. So what to do?

I believe it is better to compromise on security than on user experience. The benefits outweigh the costs. There is crime out there, but largely, there's no breakdown of society and no anarchy. Because if we compromise on freedom for the sake of security, well, you know where this leads.

All that said, if the question is how to guarantee human users can differentiate between legitimate and fake sources supposedly serving identical content, beyond what we already have, then the answer lies in another question. If you give out two seemingly identical pages to a user, what is the one piece that separates them? The immediate answer is: URL. But if the user is not paying attention to the URL, what then?

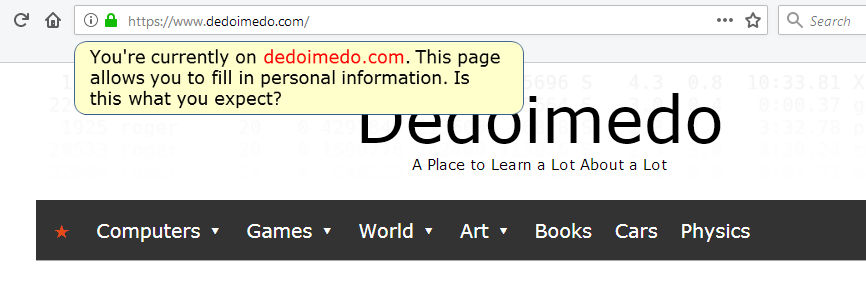

The answer to that question could be a whitelist mechanism. In other words, if a user tries to input information on a page that is not recognized (in some way) as a known (read good) source, the browser could prompt the user with something like: You're currently on a page XYZ and about to fill in personal information, is this what you expect?

Crude illustration/mockup of what could be used to warn users when they are about to provide personal information on websites that are not "whitelisted" in some way.

People might still proceed and give away their data, but hey, nothing stops people from electrocuting themselves with toaster ovens in a bath tub, either. It is NOT about changing the URL - it's about helping people understand they are at the RIGHT address. In a way that does not break the user experience.

Now, let's talk about the machine string some more, shall we.

Machine part 2

The second part needs to be standardized. Today, servers and applications parse, mangle and structure URLs any which way they want. You can add all sorts of qualifies and key pair values, and end up with things like video autoplay, shopping cart contents, pre-filled forms, and more. In a way, this is lazy, convenient coding.

The standardization needs to be neutral - not dependent on how the browser or the site wants to present its information, because it's part of the problem today (including phishing and whatnot). I think that websites need to be forced to present a simple URL structure to the user that responds in a valid way.

The answer is: URL language. The same way browsers parse HTML and CSS, there could be a URL standard for the machine part. This could be a relatively small dictionary, and it would include somewhat STILL human-readable keys like (just a small subset of possible examples):

- unique-user-identifier - this would be a value that maps to an individual browser/user.

- javascript-status - if the client supports or runs Javascript.

- media-autoplay - whether media should play.

- media-timestamp - playback position for media.

- page - navigation element.

- Other similar keys.

And the rest would be ignored by the browser - provided all browsers adhere to the international standards and offer the same behavior and responses. Yes, the same way if you invent a new CSS class or HTML directive, and it does not exist and/or hasn't been properly declared, it gets ignored. The same way the remote application should ignore non-existent standard keys.

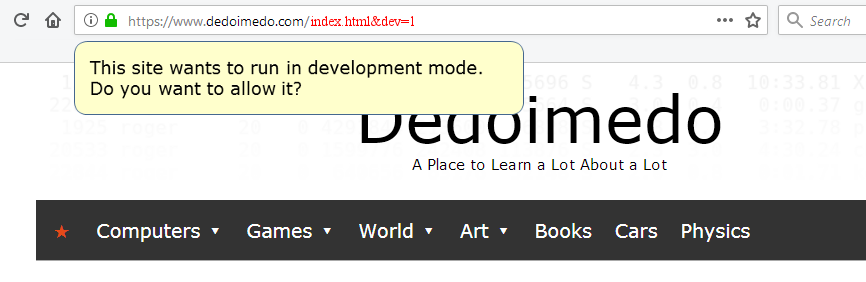

There must be special keys (flags), like dev=1 or debug=1 that would force the browser to interpret all provided machine parts and forward them to the server, which would also allow site devs/owners to troubleshoot their applications and offer full backward compatibility to everything we have on the market today. But then, the user could be prompted if such a combo is spotted in the URL address:

This site wants to run in dev mode. Do you want to allow it?

Crude illustration/mockup of what a standardized URL construct might be, with dev/debug flags.

This might enhance security too. Theoretically, the browsers could allow the user to block tracking via URL and not just on loaded pages. For instance, lots of email invitations and such come with a whole load of tracking, embedded in the URL. Privacy-conscious browsers could strip those away - or ask the user.

The URL is convenient for passing information to the application - but there's no real reason for this. When you click Buy on Amazon or PayPal, you don't see what happens. When you read Gmail, you don't see what happens. Buttons hide functionality, and it is not reflected in the URL.

To sum it up: the machine-part of the URL would contain a limited dictionary of standardized keys that would allow the information to be passed this way, but the rest would be ignored unless special flags like dev or debug are used, with the option to prompt the user. Enhanced security, enhanced privacy.

If ever defined, standardized and adopted, this will take time - an industry-wide effort. Now, is there a way to ignore forty years of legacy and existing implementations? The answer is, no bloody way. A change to the URL structure is something that will take decades. If you think IPv4 to IPv6 is complex, the URL journey will be even longer.

Finally, Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Back to square one.

Conclusion

The URL change is not important on its own - it is, but the technical part is relatively easy. The bigger issue is that, at the moment, people still have a fairly unrestricted access to the Web, largely due to the nerdy nature of the human-readable Web addresses. The URL is one of the old pieces of the Internet, and as such, it is mostly unfiltered and without abstractions. Once that goes away, we truly lose control of information. The world becomes a walled garden.

Google's general call to action makes sense, from the technical perspective, but the change could accidentally lead to something far bigger. Something sinister. Something sad. The death of the Internet as we know it. The ugly, cumbersome URL was invented in an age of innocence and exploration. As confusing as it is, it's the one piece that does not really belong to anyone. Any future change must preserve that neutrality.

If I were Google, I wouldn't worry about the URL. I would focus on why people don't want Google to be the arbiter of their Internet. Understand why people oppose you, regardless of the technical detail. Because, in the end, it's not about the URL. It's about freedom. Once that piece clicks into place, the technical solution will be trivial.

Food for thought.

Cheers.